Lisa Raynor-Keck, communication specialist at FASTORQ looks at Torque vs Tension, and whether there really is a true winner.

The debate rages on about whether torque or tension is the best method to preload a fastener, and it is nearly as controversial as the age-old question of which came first… the chicken or the egg?

Each side argues that their method is the best. However, the real question, and true heart of the matter, is whether torque or tension is the best method for each job’s specific bolting application.

“You want to analyse your bolted joints to determine when you need torque or tension,” states Bill Washington, director of business development at FASTORQ.

“I can tell you that on many flanges, they are overdesigned, and torque is fine in many cases. However, you have to use tensioners to get the bolt load you need on critical flanges.”

Bolt load

To review, torque is used to turn a nut, to stretch a bolt, and provide clamping force. It is usually done with a manual, hydraulic or pneumatic torque wrench. Tension produces stress, or load, on a fastener. The result is strain. This is where the material in the bolt wants to return to its original state. This can be achieved with a hydraulic stud tensioner that directly pulls the desired bolt load into the fastener and with a nut turned down to hold it. Both methods work to achieve bolt load and have their pluses and minuses.

“When proper preload is applied and maintained, regardless of the equipment used to load the bolts in a joint, the bolt cannot fail from fatigue, because it will experience no change in stress,” according to Washington. “Anyone can cause any fastener to fail by simply over tightening or under tightening it.”

The problems caused by incorrectly loading any system can be catastrophic, Washington says. Whether it’s a piping flange in a refinery that ultimately causes a fire or a wind turbine that comes down, “turbine and all,” when a bolt in the hub hasn’t been properly tightened, proper bolt load on critical joints is essential. The bolted joint can be the “weakest link”.

The best way to avoid catastrophic results from bolt load failure, Washington explains, is to follow proper operation procedures and work practices when using torque and by using load indicating washers or an ultrasonic extensometer to measure preload. However, in the absence of a way to measure preload, then tension may be the best option.

Torque

“Torque is OK, and is widely used in a lot of applications,” Washington says. “Torque is a relatively inexpensive option to tighten bolts, and it can do well on most jobs.”

Yet, the problem with applying torque, notes Washington, is people must understand all of the things that “get in the way of applied torque resulting in desired bolt load”. This problem can be summarised as ‘K’ Factor or nut factor.

“The big problem with torque is that we have a lot of things going on,” Washington explains.

Several factors make up the ‘K’ Factor, including contaminants, rust, lubricant, bolt fit, washers and surface condition that could allow embedment. All of these factors, and more, will impact resulting preload.

“The problem with ‘K’ Factor is that you can try to predict it the best you can based on experience, but it is an experimental factor, which means you can’t get ‘K’ unless you’ve already tightened the bolt and measured the bolt load. Now you know, after the fact, what ‘K’ was and not what it will be,” Washington says. “The problem is if you don’t consider it at all, you are certainly going to be wrong.”

Even with a good procedure utilising a crisscross pattern to apply torque in steps at 30%, 70%, 100% of final torque, with a 100% circular, it takes time and still may not be accurate. If a person takes shortcuts, Washington says, “You can pinch a gasket and actually cause the joint to leak.”

As a way of overcoming ‘K’ Factor problems, bolt preload can be measured by using an ultrasonic extensometer. The biggest problem with these machines is that they are very expensive and many people do not know how to operate them. Another less expensive and simpler option to accurately measure bolt load is by using a load-indicating washer, also known as a Direct Tension Indicator (DTI). Washington explains that a person can be trained to use a load-indicating washer within 30 seconds.

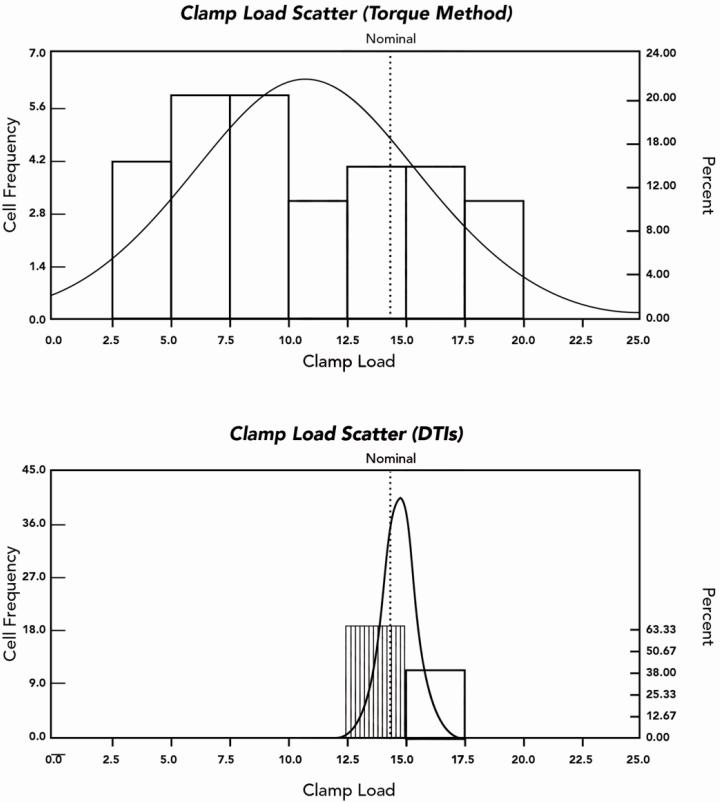

As the two graphs, indicate, the actual clamp load generated while using the torque method shows a tremendous amount of variation, while that generated by using load-indicating washers (DTI) is remarkably consistent. The DTI tension method is far more accurate than the torque method.

As the two graphs, indicate, the actual clamp load generated while using the torque method shows a tremendous amount of variation, while that generated by using load-indicating washers (DTI) is remarkably consistent. The DTI tension method is far more accurate than the torque method.

Despite several conditions that can significantly affect bolt load when using torque, some situations call for it, such as when there is limited clearance and stud tensioners cannot fit. Since only one nut can be turned at a time, Washington encourages users to find a strong and fast torque wrench, such as a SpinTORQ, which minimises the time it takes to complete a bolted joint.

“Time is money. For mounting blades to hubs, you may want to use a torque wrench. By using a standard hydraulic torque wrench to torque those bolts, it can take a lot of time,” Washington says. “Using a SpinTORQ to torque those bolts takes less than one fifth of the time.“

Tension

“Tensioning systems compared to torque wrenches can cost 10x, 20x, 30x as much as torque wrenches. So it’s a big investment for stud tensioners,” Washington explains. “If you have a problem flange, and it is critical that your bolt load be evenly distributed, you want tensioning.”

When numerous bolts need to be tightened on a flange, tensioning is the fastest and most reliable way to achieve even bolt preload, according to Washington. Tension can reduce or eliminate elastic interactions depending on the coverage, minimise or eliminate potential over-compression of gaskets, and eliminate many of the obstacles torque has when achieving desire preload.

“If maintenance is to be done and you need to get a unit back online, it’s really just a matter of how fast you want to get the job done,” Washington says. “Bolting is one of those things that gets in the way of getting things back online quickly.”

“With fixed and variable stud tensioners that run at 20,000 psi, it’s difficult to fit the load cells side by side (due to their size), and they will need to be screwed on by hand. Fifty percent coverage of the bolts is typical, anything less and people start to run into the same problems they have with torque,” states Washington. “Elastic interactions, along with uneven bolt load can occur. With these type of tensioners, the first half of stud tensioners need to be set at a higher tension to compensate for the residual load from the second half of the tensioners that are put on the flange.”

Additional downsides with stud tensioners include: higher load on the first pass can cause over-compression of gasket material; additional bolt length is required; they are an expensive investment; most fit only one size bolt and the applied preload doesn’t always guarantee desired clamping force.

Tensioning is faster than torque and there are multiple types of tensioners available on the market today including traditional fixed tensioners, variable tensioners and ZipTENSIONERs

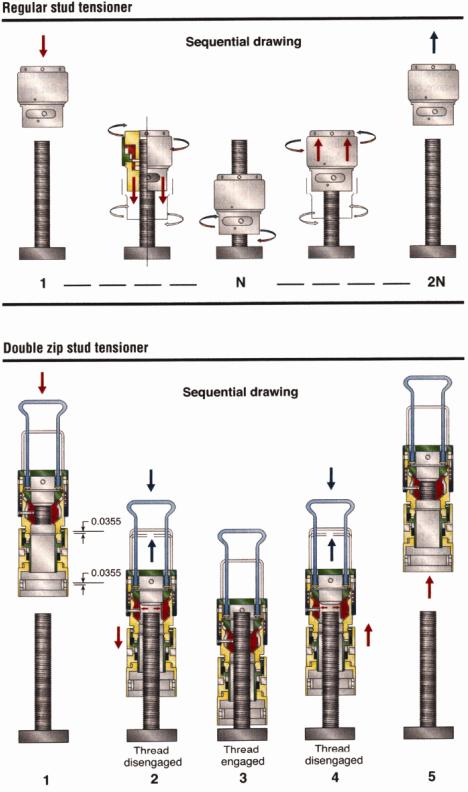

Another alternative to fixed and variable stud tensioners is the ZipTENSIONER. One hundred percent coverage is possible with these tensioners on the same side of the flange, and they reduce residual load problems. Also, these stud tensioners remove the tedious on and off threading involved with positioning conventional stud tensioners on a flange. They are able to do this since their reaction nut is a ZipNut®, which was originally designed for NASA for use on the Space Shuttle, International Space Station and to repair the Hubble Telescope. ZipNut has spring-loaded thread segments that slide down the bolt. When the tensioner is engaged, they grab onto the bolt, lock in mechanically and then can slide back off without having to thread anything on or off.

“The ZipTENSIONERs are different. The time savings are huge. You can reduce the time it takes to tension a flange by 80% to 90%. We go to a higher pressure range of 30,000 psi; we’ve reduced the load cell area and we can get 100% coverage on the same side of the flange,” explains Washington.

“The ZipNut reaction nuts don’t cross thread or have problems with the condition of the bolt. I can pull all of the bolts into tension simultaneously and be done. For gasket seating stress, it’s ideal because I’m evenly loading, with evenly distributed bolt load, the entire flange simultaneously.”

Contributing factors

“It is important for wind turbine design engineers to consider critical bolted joints and whether they should use torque or tension,” Washington says. “This matter should not be an afterthought.”

“Engineers need to make sure that they allow enough room for the tools. Sometimes they don’t always allow the proper clearances for these tools to be installed on a bolt and work properly,” according to Washington. “Many times that causes work-arounds.”

Other factors that make a difference in torque and tension are use of lubricants and the reuse of nuts and bolts.

“A good lubricant with a sufficient amount of solids is always critical, whether you are torqueing or tensioning. Any old lubricant is not OK. You want the nuts to spin as freely as possible on the bolts to obtain the load that you need with the required torque,” Washington advises. “You also want a lubricant that allows you to have enough residual on a bolt so that there is something there between the nut and bolt when you are ready to break it loose.”

He also warns that reusing nuts and bolts is not a sound idea unless it can be assured that their integrity has not been compromised over time, since it can affect their performance.

The winner

So, which method is the clear winner? Just like the chicken and egg question, it all depends on perspective.

“You’ve got to make some decisions about torque vs tension based on performance requirements and budget,” Washington explains. “If you base your decision on torque vs tension strictly on budget, irrespective of performance, and if you have a problem flange, you’ll blow the budget and then some trying to fix it.”

Mainly, it is necessary to understand your needs, according to Washington. If you have a lot of bolts to tighten, torque with a high quality torque wrench and load indicating washers is a good way to go.

However, if you have a critical joint and you want the most accurate results and even bolt load, tension is worth the money, especially with stud tensioners that are designed to be efficient and save time.

Having spent a decade in the fastener industry experiencing every facet – from steel mills, fastener manufacturers, wholesalers, distributors, as well as machinery builders and plating + coating companies, Claire has developed an in-depth knowledge of all things fasteners.

Alongside visiting numerous companies, exhibitions and conferences around the world, Claire has also interviewed high profile figures – focusing on key topics impacting the sector and making sure readers stay up to date with the latest developments within the industry.